On the night of December 3, I was staying at the Park Central Hotel in NYC. I usually stay at the Warwick, which is cattycorner to the Hilton, but the next day was the tree lighting and midtown pricing was nuts. Still, I was only a block away so the sirens startled me awake at 6:50 the next morning. “Welcome to New York,” I grumbled, remembering 35 years of interrupted sleep when I lived in Manhattan. I made some coffee and got ready for the day.

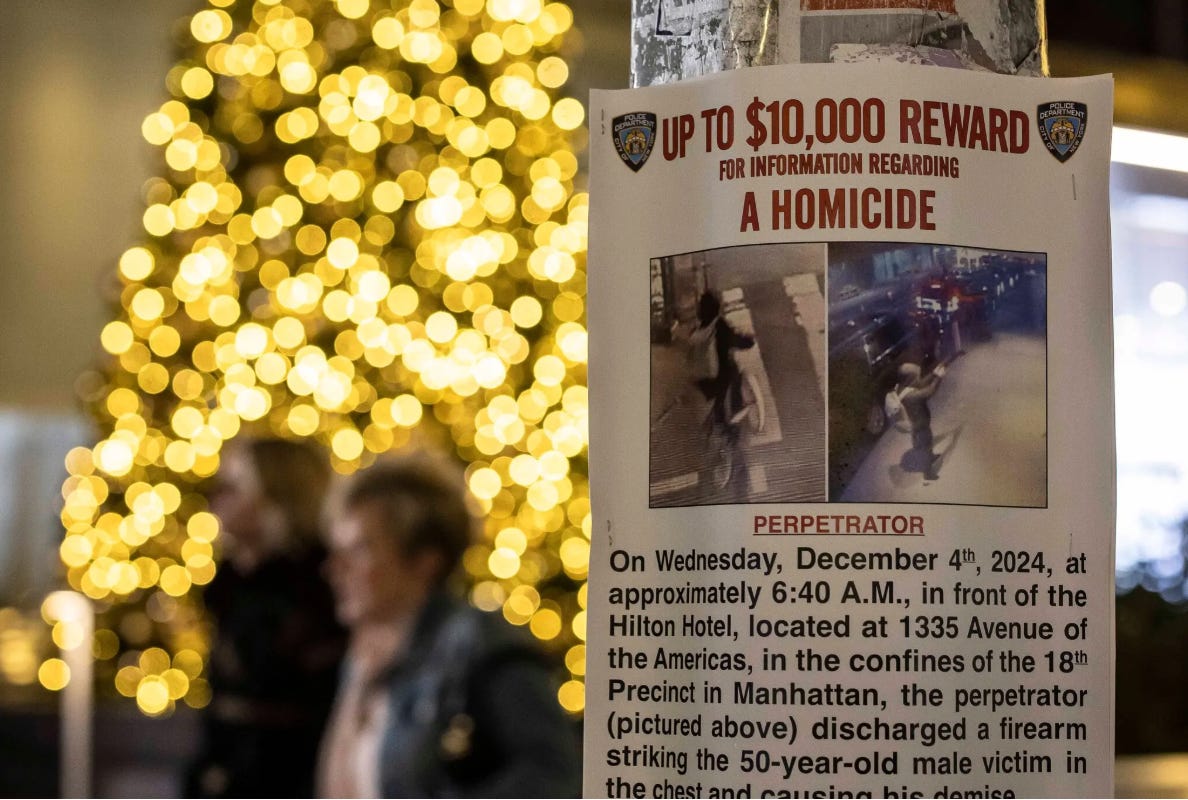

But two hours later, walking down 55th Street it became clear that this was no ordinary morning in NYC. Cops— far more than needed to escort Christmas revellers— were everywhere and the streets near 6th Avenue were blocked. Perhaps a terrorist was targeting the tree lighting, I figured. But no, it was the manhunt for the killer who’d gunned down United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson as he left the Hilton at 6:45 for an investor meeting.

As noted last week, I’ve been avoiding the news since November 5, so I hadn’t checked my phone for headlines. But the owner of Escape, the salon where I had an appointment and that I’ve patronized since 1990, had just been interviewed by the police, so she caught me up and I immediately became obsessed. Throughout the day, I found myself reverting to my old news-addict behavior, though limited to this particular event.

The details were so New York, like a parody of a Law & Order episode: the shooter yucking it up at Starbucks before the hit, the stunningly graphic CCTV images, the Citibike rental and the escape through Central Park. Even the professional touch in the choice of the gun built for stealthy assassination, and the high-end, hipster backpack the killer wore.

It took me back to the baroque details, though with a different aesthetic, of those mob hits of the ‘70s and ‘80s that had riveted New York: Joey Gallo at Umberto’s Clam House, Carmine Galante at Joe and Mary’s, Paul Castellano at Stark’s Steak House. I’d been to Umberto’s and Stark’s. And Galante had frequented the 2nd Avenue café where I first learned to like espresso. A strange feeling of personal connection to these events helped to inspire my early career as a crime reporter.

Of course, Brian Thompson was a respected executive, not a mobster. He was born in Iowa and lived in Minnesota, for God’s sake. Yet the instinctive and widespread response– “probably someone who was denied coverage”– and the shocking vitriol that greeted the news of his death– “sorry, but my thoughts and prayers are out-of-network”– suggest that many Americans have come to view the health insurance industry as a form of racketeering.

This is hardly surprising. Over the past two years, 75% of healthcare providers– doctors and hospitals– reported an increase in claim denials, according to a Senate report released last month. Obamacare reported a 17% increase while denials for some Medicare Advantage policies increased by 54%. Private insurers are assumed to have even higher denial rates, though insurers keep specific details private.

The Senate report also cited United Healthcare— one of the biggest insurers— as one of the companies that reaped the greatest financial benefits from these practices.

We can’t know whether Brian Thompson wanted to try to reverse this trend. Or if he cared that health insurance profits are surging even as the actual health of Americans declines and medical bankruptcies soar. His violent death will of course in no way address these problems, and given the present political climate, the most likely result will be a lot of solemn opinion pieces, along with a feast of conflicting accusations.

But I’m struck that the cynicism that was once particular to New York’s brand of glamour back in the mob-hit era has begun to pervade the culture at large. Doctors and medical technicians now routinely excoriate healthcare insurers to their patients, while patients offer their own ugly tales in response. In this climate, the gunning down of a high-profile executive in front of an iconic Manhattan hotel has an air of inevitability about it.

The cynicism that has come to pervade any discussion of health care is poisoning our faith in the business sector, which has always served as a chief engine of America’s outsized success, along with our unparalleled ability to assimilate people from vastly different cultures. Both capacities are now in different ways under attack, with consequences from New York to Minnesota and beyond, as witnessed by the shooting's culprit having thrown away a bright future for which he was well prepared and in a position to make happen.

This cynicism is also a chief reason our nation continues to be divided, since it undermines our ability to feel and show sympathy for those we perceive as having different values, be they Central American families selling candy bars on 5th Avenue or CEOs lying in a pool of blood on 6th.

Finally, cynicism makes us more likely to tolerate the systemic corruption that has begun to pervade our institutions, which feeds greater cynicism in its turn. We become like the man I passed as I rounded the corner of 55th Street on the cold morning of the shooting. We shrug and repeat that characteristic New York refrain: What’re ya gonna do?

Like what you’re reading? Click here to order my most recent book Rising Together, or How Women Rise, both are available from Amazon or from your favorite bookseller.

“Finally, cynicism makes us more likely to tolerate the systemic corruption that has begun to pervade our institutions, which feeds greater cynicism in its turn.”

The most poignant part for me. I wonder if this might be one of the hardest yet most important changes that someone can make, because it requires them to change their personal POV on what’s possible, despite not immediately seeing evidence of that yet.

What are some ways you think people can start to rewire their cynicism?

Thanks Jonathan. This article is particularly helpful to me as I'll be addressing an insurance company event in February. I just skimmed it but have saved it for when I need it.

A good perspective. Maybe what happened on Dec 4 will create greater support for the humane approach you advocate.