We rise together by demonstrating solidarity with those we perceive as different from ourselves, offering them resources, access and support. This kind of intentional allyship has particular power when used to spur social change by forging bonds with those who’ve been marginalized.

I’ve been thinking about this after reading an article about Jeanne Manford, an unassuming elementary school teacher from Queens, NY. Jeanne helped change the world by embodying the notion that we cannot rise unless we do so together.

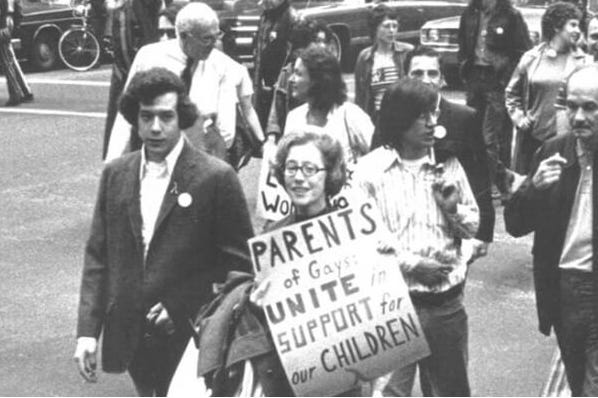

I remember Jeanne vividly from her remarkable appearance at the 1972 Christopher Street Liberation Day March, which later evolved into the NYC Gay Pride Parade. I lived near Christopher Street at the time and came out to watch the march, then in its second year. Amid young men in bell bottoms and tie-dyed t-shirts or toned, bare chests and sprinkling of bouffanted drag queens, there suddenly appeared a nerdy 52-year-old woman in glasses, a cardigan and pearls carrying a sign that read Parents of Gays Unite in Support of Our Children.

The sign was startling, for it simply never occurred to most people in 1972 that the parents of gay children would publicly (or even privately) support them, much less march in solidarity with other members of this then-rejected tribe. Jeanne Manford’s very public action– her picture was suddenly all over the news– signaled a shift toward what over time would become widespread acceptance of children like her son, Morty. Not just by parents, but by social and political organizations, as well as employers and landlords.

Jeanne Manford’s radical demonstration of solidarity proved a turning point because what we now call the LGBTQ community had, until she held up her sign, been mostly on its own. For example, the proper and polite 1950s Mattachine Society, the first group to advocate for gay rights, had produced few allies due to the repressive social codes of the era, as well as the founders’ roots in the Communist Party.

The Gay Liberation movement was different: hardscrabble, proud, defiant and uber-democratic. It was born out of the Stonewall riot, which began when patrons at a well-known Christopher Street gay bar resisted being carted off in vans by police conducting one of the post-midnight raids they regularly staged on establishments that served alcohol to gay men or women. My boss at the time, Howard Smith, had caught wind of the story, raced out to cover it for the newspaper we worked for, and ended up barricaded inside the bar all night.

In his article for The Village Voice, Howard noted the precise nature of what made the resistance so powerful. The men that the police were attempting to round up refused to hide their faces or shrink from the photographers who gathered throughout the night, a routine demonstration of shame that had always been part of the gay-raid ritual. The Stonewall patrons were sufficiently sick of their mistreatment at the hands of the police and the wider public that they lost the fear of disgrace that had for so long kept them in the shadows.

Yet for the most part, their families had not lost the fear of stigma that led them either to reject their gay children or to practice some version of don’t-ask-don’t-tell. That’s why Jeanne Manford’s let-the-world-know-it action felt so revolutionary. Here she was, very publicly breaking what until then had seemed a universal taboo by simply insisting that a parent’s love for their child was stronger than the weight of law or tradition.

The rising together aspect of this story is demonstrated by Jeanne’s recognition, even as she marched the fifty blocks from Christopher Street to Central Park, that organizing support from other parents would be critical to the movement’s success. The courage shown by gay people, who after all were subject not only to arrests and beatings but vulnerable to losing their jobs and homes just for coming out, needed to be matched by their families. Which meant that parents had to come out too.

So Jeanne undertook the basic work of organizing, traveling to persuade on-the-fence parents to set up their own support groups, an effort that soon spread to cities and towns around the world. These groups would prove of inestimable value in the 1980s when AIDS took so many lives: among them Morty Manford, Jeanne’s son. Like any disaster, AIDS demonstrated the truth of the psalmist’s words, that love is stronger than death.

So is the organizing that manifests this love.